There is a compromise between brightness and fire if you want ideal proportions/light performance and this is known as the cutter’s trade-off. In general, a diamond with a higher crown and a steeper crown facet will produce more fire. Fire in a diamond is primarily determined by the size and angle of the crown facets. In the previous tutorial, I explained how fire is the colored light you see in a diamond. This is why you need to know what you’re looking at when making comparisons. Shallower cut diamonds will have greater light obstruction than diamonds that are cut deep. In general, the closer you view the diamond, the greater the light obstruction. The range of angles where obstruction is visible is dependent on the viewing distance and the particular combinations of facets. But when there is no light obstruction, what you will find is that weaker light return under the table creates a stronger contrast with the arrows than in a diamond with strong light return. When there is strong light return under the table and the arrows are black, the arrows stand out creating a strong contrast. At normal viewing distances, the arrows obstruct light and you get darker arrows. You see, in pictures of diamonds where you see black arrows, what you’re actually looking at is a reflection of the black camera lens. The steep/deep diamond was less bright under the table facet and against this weaker light return the arrows were clearly more visible. I looked at the diamond and it was obvious that this was indeed the case.

Kenny explained to me that it was because the arrows pattern stood out more clearly to him. Under the idealscope, he was surprised that the diamond he chose had very obvious light leakage under the table facet. He didn’t mind telling me his honest opinion that he actually preferred the diamond with the 35CA/41PA. When we put the diamonds side-by-side, I asked Kenny to tell me which diamond he liked better. In theory, a 34.5/40.8 CA/PA produces ideal light return. My wife was there at the time so we had her diamond, which was a 34.5CA/40.8PA, to use as a comparison stone. On the GIA report, it showed that the crown angle was 35 degrees and the pavilion angle was 41 degrees. At one point we saw a stone that had a slightly steep crown angle and a slightly steep pavilion angle. I was helping my best friend Kenny pick a diamond for his engagement ring. Let me explain what I mean with a story from my very first diamond consultation. In fact, many branded super-ideal diamonds have a structured contrast that doesn’t maximize light return under the table. The point here is that some people will prefer overall brightness, and others will prefer a different kind of structured contrast. I call the combination of these different types of effects structured contrast. The contrast pattern you see in a diamond can be created with intense light return, weak light return, light obstruction, and even light leakage.

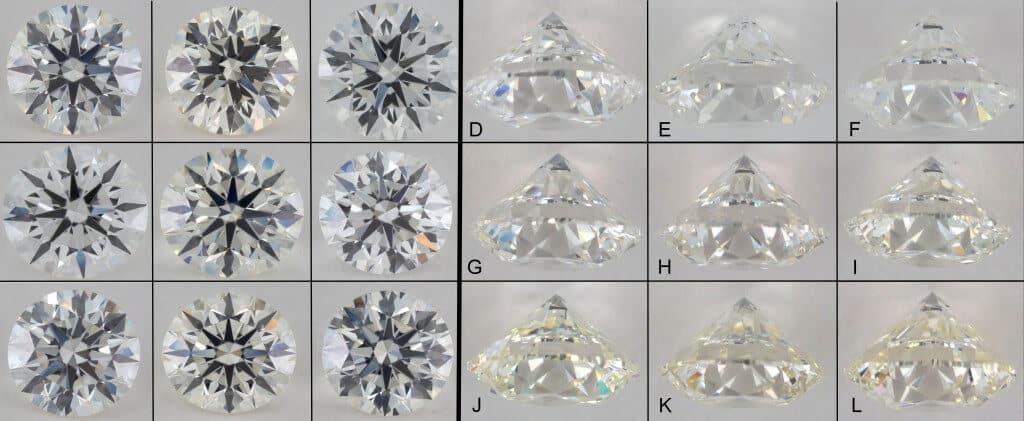

Contrast, which refers to the difference in brightness levels, can be quite subjective. In diamonds, brilliance is the combination of brightness and contrast.īrightness is the objective part of brilliance because it is something that can be measured. In this tutorial, I will explain to you what brilliance, fire, and scintillation is and help you determine your light performance preferences. But most importantly, I touched on the fact that 100% light return does not necessarily translate to a beautiful diamond. I also showed you that the direction from where light is being returned has a big effect on the strength of that light return. In part one, I explained why light return is important and why you want to avoid light leakage in a diamond. The unique proportions and the optical symmetry of a diamond will give each diamond a slightly different light performance profile. Light performance can be broken down into brilliance (brightness), fire, and scintillation (sparkle).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)